How Much Money Do The Rich Give To Charities

P hilanthropy, it is popularly supposed, transfers money from the rich to the poor. This is non the case. In the US, which statistics show to be the nearly philanthropic of nations, barely a fifth of the money donated by big givers goes to the poor. A lot goes to the arts, sports teams and other cultural pursuits, and one-half goes to educational activity and healthcare. At first glance that seems to fit the popular profile of "giving to good causes". But dig down a piddling.

The biggest donations in teaching in 2019 went to the elite universities and schools that the rich themselves had attended. In the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, in the 10-year flow to 2017, more than two-thirds of all millionaire donations – £iv.79bn – went to higher instruction, and half of these went to simply two universities: Oxford and Cambridge. When the rich and the middle classes give to schools, they give more to those attended by their own children than to those of the poor. British millionaires in that same decade gave £1.04bn to the arts, and merely £222m to alleviating poverty.

The common assumption that philanthropy automatically results in a redistribution of money is wrong. A lot of elite philanthropy is almost elite causes. Rather than making the world a better identify, it largely reinforces the world as it is. Philanthropy very often favours the rich – and no one holds philanthropists to account for it.

The role of private philanthropy in international life has increased dramatically in the past two decades. Nearly three-quarters of the world's 260,000 philanthropy foundations have been established in that fourth dimension, and betwixt them they command more than $1.5tn. The biggest givers are in the U.s.a., and the UK comes 2d. The scale of this giving is enormous. The Gates Foundation alone gave £5bn in 2018 – more than than the foreign aid budget of the vast majority of countries.

Philanthropy is always an expression of power. Giving often depends on the personal whims of super-rich individuals. Sometimes these coincide with the priorities of society, but at other times they contradict or undermine them. Increasingly, questions take begun to be raised about the impact these mega-donations are having upon the priorities of club.

There are a number of tensions inherent in the relationship between philanthropy and democracy. For all the huge benefits modern philanthropy can bring, the sheer calibration of contemporary giving can skew spending in areas such as education and healthcare, to the extent that it can overwhelm the priorities of democratically elected governments and local authorities.

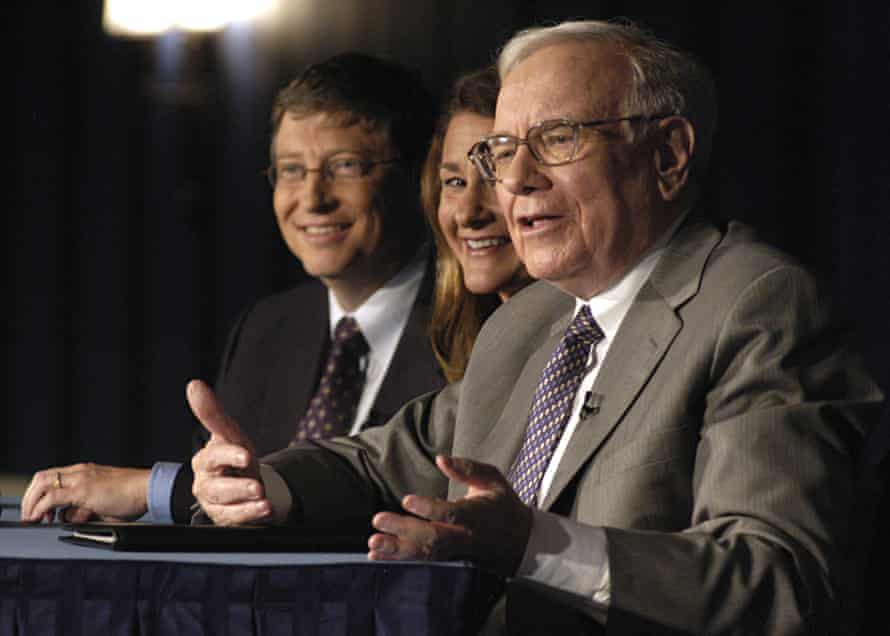

Some of this influence is indirect. The philanthropy of Bill and Melinda Gates has brought huge benefits for humankind. When the foundation made its start big grant for malaria research, it virtually doubled the amount of money spent on the illness worldwide. Information technology did the aforementioned with polio. Thanks in function to Gates (and others), some 2.five billion children have been vaccinated against the affliction, and global cases of polio accept been cutting past 99.9%. Polio has been virtually eradicated. Philanthropy has made practiced the failures of both the pharmaceutical industry and governments across the world. The Gates Foundation, since it began in 2000, has given abroad more than $45bn and saved millions of lives.

Notwithstanding this approach can be problematic. Pecker Gates can become fixed on addressing a problem which is non seen as a priority by local people, in an area, for instance, where polio is far from the biggest trouble. He did something similar in his education philanthropy in the US where his fixation on grade size diverted public spending away from the actual priorities of the local community.

Other philanthropists are more than wilfully interventionist. Individuals such as Charles Koch on the correct, or George Soros on the left, have succeeded in altering public policy. More than $10bn a year is devoted to such ideological persuasion in the Us alone.

The effect has been what the late German billionaire shipping magnate and philanthropist Peter Kramer chosen "a bad transfer of power", from democratically elected politicians to billionaires, so that it is no longer "the land that determines what is good for the people, only rather the rich who decide". The Global Policy Forum, an independent policy watchdog that monitors the work of the United nations general associates, has warned governments and international organisations that, before taking money from rich donors, they should "appraise the growing influence of major philanthropic foundations, and peculiarly the Pecker & Melinda Gates Foundation … and analyse the intended and unintended risks and side-furnishings of their activities". Elected politicians, the UN watchdog warned in 2015, should be particularly concerned most "the unpredictable and bereft financing of public appurtenances, the lack of monitoring and accountability mechanisms, and the prevailing practise of applying business logic to the provision of public appurtenances".

Some kinds of philanthropy may have go not but non-autonomous, but anti-autonomous. Charles Koch and his tardily brother, David, are undoubtedly the most prominent example of rightwing philanthropy at work. But at that place are scores of others, almost particularly in the Us, who comprehend causes which many find controversial and even distasteful. Art Pope has used the fortune he has amassed from his discount-shop chain to push for a tightening of the law to forbid fraud in elections, even though such fraud is negligible in the Us. Pope'south movement, which would require voters to show ID at the polls, finer disenfranchises the x% of the electorate who lack photograph ID considering they are too poor to own a motorcar and are unlikely to get to the expense of getting a driving licence or other ID simply to vote. Such voters – many of them black – are statistically unlikely to vote for the arch-conservatives that Art Pope smiles upon.

Simply do such philanthropic activities manipulate the democratic process any more than exercise the campaigns of the billionaire financier George Soros to promote accountable regime and social reform effectually the earth? Or hedge-fund billionaire Tom Steyer's funding of a motion to encourage more immature people to vote on climatic change? Or the attacks past the internet billionaire Craig Newmark on false news? In each case these rich individuals are motivated to intervene by something arising from their own lived experience. By what yardstick can we advise that some are more legitimate than others?

David Callahan, the editor of the Inside Philanthropy website, puts information technology this fashion: "When donors hold views nosotros detest, nosotros tend to see them as unfairly tilting policy debates with their money. Yet when we like their causes, nosotros often view them as heroically stepping forrad to level the playing field against powerful special interests or backward public majorities … These sort of à la carte reactions don't make a lot of sense. Really, the question should exist whether we retrieve information technology'due south OK overall for any philanthropists to have so much power to accelerate their own vision of a ameliorate society."

T he idea that a philanthropist'due south money is their ain to do with as they delight is deep-rooted. Some philosophers argue that each private has full ownership rights over their resources – and that a rich person'south only responsibility is to employ their resources wisely. John Rawls, one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, saw justice equally a affair of fairness. He argued that citizens discharge their moral responsibility when they contribute their fair share of the taxes which governments utilise to take care of the poor and vulnerable. The better-off are and so gratis to dispose of the rest of their income every bit they like.

But what the rich are giving away in their philanthropy is not entirely their ain money. Tax relief adds the money of ordinary citizens to the causes chosen by rich individuals.

Near western governments offer generous taxation incentives to encourage charitable giving. In England and Wales in 2019, an individual earning upward to £fifty,000 a year paid 20% of information technology in income tax. For those earning more, annihilation between £50,000 and £150,000 was taxed at forty%, and annihilation above £150,000 was taxed at 45%. But gifts to registered charities are tax free. And so a souvenir of £100 would cost the standard taxpayer merely £80, with £xx existence paid past the government. But the highest-rate taxpayer would need to pay out but £55, because the state would provide the other £45. Super-rich philanthropists, therefore, find themselves in a position where a large percentage of their souvenir is funded by the taxpayer. Thus it becomes far less articulate whether the money philanthropists give abroad can rightfully exist regarded as entirely their ain. If taxpayers contribute function of the gift, why should they not have a say in which charity receives it?

In Britain, the total price to the state of the various tax breaks to donors in 2012 was estimated past the Treasury at £three.64bn. Revenue enhancement exemptions for charities have existed in the Great britain since income tax was introduced in 1799, though charities had been largely exempt from certain taxes since the Elizabethan age. Indeed, British revenue enhancement relief is nevertheless largely confined to the categories of clemency set out in the 1601 Charitable Uses Act, which lists four categories of charity: relief of poverty, advancement of instruction, promotion of religion, and "other purposes benign to the community". There are even fewer limitations on bodies wishing to become tax-exempt charities in the United states, across a requirement not to engage in party politics.

Both countries offer additional incentives where donations are made to endow a charitable foundation. This enables a philanthropist to escape liability for tax on the donation, nonetheless also retain control over how the money is spent, within the constraints of charity law. The effect of this is often to give the wealthy control in matters that would otherwise be adamant past the state.

Yet the priorities of plutocracy, rule by the rich, and democracy, rule by the people, oftentimes differ. The personal choices of the rich practise non closely lucifer the spending choices of democratically elected governments. A major enquiry study from 2013 revealed that the richest i% of Americans are considerably more than rightwing than the public as a whole on issues of taxation, economical regulation and especially welfare programmes for the poor. Many of the richest 0.1% – individuals worth more $40m – want to cut social security and healthcare. They are less supportive of a minimum wage than the balance of the population. They favour decreased government regulation of large corporations, pharmaceutical companies, Wall Street and the City of London.

"There is expert reason to be concerned about the impact on democracy if these individuals are exerting influence through their philanthropy," wrote Benjamin Page, the atomic number 82 academic on the study. The asymmetric influence of the mega-wealthy may explain, information technology concluded, why certain public policies announced to deviate from what the majority of citizens want the regime to practice. The choices fabricated past philanthropists tend to reinforce social inequalities rather than reduce them.

In that location is therefore a strong argument that the money donated by philanthropists might be put to ameliorate employ if information technology were collected as taxes and spent according to the priorities of a democratically elected authorities. In which example, should the state be giving tax relief to philanthropists at all?

T he instance for tax reform – to abolish these subsidies entirely, or ensure the rich can merits no more than than basic tax payers can – has been made from both the right and the left. Taxation breaks distort market choices, argues a prominent libertarian, Daniel Mitchell, of the Cato Found, a thinktank funded by the conservative philanthropist Charles Koch. At the other finish of the political spectrum, Prof Fran Quigley, a man rights lawyer at Indiana University, argues that charitable taxation deductions should be concluded – to free upwardly billions of dollars for increased public spending on "food stamps, unemployment compensation and housing assistance". But they should as well stop because they bolster the morally dubious illusion that charity "constitutes an constructive and acceptable response to hunger, homelessness, and illness".

Withal attempts by politicians to limit the corporeality of tax relief – let alone abolish information technology entirely – take met with public disapproval ever since William Gladstone tried to cut information technology in 1863. The same matter happened when the British government tried to address the issue in 2012. When chancellor George Osborne tried to limit the corporeality of tax relief the rich could claim on their giving, he provoked a mass outcry from philanthropists, the press and from charities. Similar attempts at reform by President Barack Obama in the The states met the same fate.

An alternative solution might exist to impose restrictions on the kind of causes for which tax exemptions tin be claimed. At the final election, the Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn floated the thought of removing charitable status from fee-paying schools. Others become further. "Donations to higher football teams, opera companies and rare-bird sanctuaries are eligible for the aforementioned taxation deduction every bit a donation to a homeless shelter," complains Quigley. 1 of the most thoughtful contemporary defenders of philanthropy, Prof Rob Reich, managing director of the Center on Philanthropy and Ceremonious Society at Stanford University, who has described philanthropy as "a form of ability that is largely unaccountable, un-transparent, donor-directed, protected in perpetuity and lavishly tax advantaged", sees the respond in restricting tax relief to a hierarchy of approved causes.

Merely who decides that bureaucracy? The problem comes in finding a machinery that would better marshal charitable giving with by and large agreed conceptions of the common good. Of course, it could exist left to the land. But as Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, told me: "That's giving the state a dangerously high level of discretion. The more the state takes on a role of moral scrutiny, the more than I worry … and the history of the last 100 years ought to tell us that a hyper-activist state with lots of moral convictions is pretty bad for everybody."

Others accept seen the solution equally just increasing taxes on the mega-rich. When the Dutch economic historian Rutger Bregman was asked at Davos in 2019 how the globe could prevent a social backlash rising from the growth of inequality, he replied: "The respond is very simple. But stop talking about philanthropy. And start talking about taxes … Taxes, taxes, taxes. All the balance is bullshit, in my opinion."

The idea of greater taxes on the rich is gaining buy politically all over the earth. During the Democratic party presidential primaries, several candidates set out proposals for raising taxes on the avails or income of the super-rich. The growing economic populism across Europe and in the US will increase that force per unit area. So will the need to increase public revenue to see the cost of the coronavirus crunch.

A number of prominent philanthropists, including Warren Buffett and Neb Gates, take publicly backed the idea. "I've paid more taxes than any private always, and gladly so. I should pay more," Gates has said. Buffett says "society is responsible for a very significant percentage of what I've earned", so he has an obligation to give back to society. Another rich entrepreneur, Martin Rothenberg, founder of Syracuse Language Systems, spells out how public investment makes private fortunes possible. "My wealth is not only a product of my own hard work. It also resulted from a strong economy and lots of public investment, both in others and in me," he said. The country had given him a skilful education. There were complimentary libraries and museums for him to employ. The government had provided a graduate scholarship. And while teaching at university he was supported by numerous enquiry grants. All of this provided the foundation on which he built the company that made him rich.

All of this undermines the argument that the rich are entitled to keep their wealth considering information technology is all a effect of their hard work. Indeed, some overtly admit the existence of this social contract. In the UK, Julian Richer, founder of the hi-fi concatenation Richer Sounds, transferred 60% of the ownership of his £9m company to his employees in a partnership trust in 2019. Asked why he had made this decision, he replied that the staff had demonstrated loyalty over 4 decades, so he was at present "doing the right thing" because that way "I sleep better at night."

T he growth in philanthropy in recent decades has failed to curb the growth in social and economic inequality. "Nosotros should expect inequality to decrease somewhat as philanthropy increases … It has non," writes Kevin Laskowski, a field associate at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. Indeed, as Albert Ruesga, president and CEO of the Greater New Orleans Foundation, has noted, "the collective deportment of 90,000+ foundations … subsequently decades of work … have failed to alter the virtually basic conditions of the poor in the US."

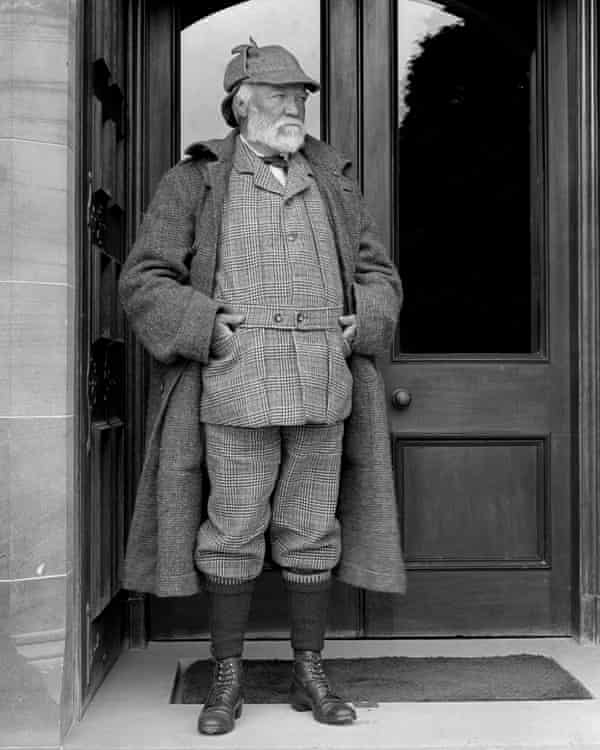

Why? The respond lies in the template that was established by the men who transformed modern philanthropy through the sheer scale of their giving in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For all their munificence, the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie and the great industrial philanthropists of that era were notable – even in their ain day – for fugitive the whole question of economical justice. And so, as at present, a huge percent of wealth was in the easily of a tiny few, almost completely untrammelled by tax and regulation. Carnegie and his fellows, their critics said, neglected the great upstanding question of the twenty-four hour period, which centred on "the distribution rather than the redistribution of wealth". Carnegie, then the richest man in the earth, was criticised in his day for distributing his unprecedented largesse because his fortune was built on ruthless tactics such equally cutting the wages of his steel-workers. Carnegie's greatest contemporary critic, William Jewett Tucker, concluded there is "no greater mistake … than that of trying to brand clemency do the work of justice".

Carnegie built a network of nearly 3,000 libraries and other institutions to help the poor elevate their aspirations, but social justice was entirely absent from his agenda. More that, he and his young man "robber baron philanthropists" faced questions on the source of the coin with which they were and so generous – for information technology had been accumulated through business organization methods of a new ruthlessness. Like many of today's tech titans, they amassed their vast fortunes through a relentless pursuit of monopolies. Teddy Roosevelt'south judgement on John D Rockefeller was that "no amount of charity in spending such fortunes can compensate in whatsoever way for the misconduct in acquiring them". Information technology is an insight that has found renewed traction in our times – equally was shown past the ostracism of the Sackler family as leading international art philanthropists in 2019, and the boycotting of BP's sponsorship by cultural leaders including the Royal Shakespeare Visitor. Roosevelt'southward judgment on reputation-laundering through philanthropy is gaining new currency.

Philanthropy can be compatible with justice. But it requires a conscious effort on behalf of philanthropists to brand it so. The default inclines in the opposite direction. Reinhold Niebuhr, in his 1932 book Moral Man and Immoral Gild, suggests why: "Philanthropy combines genuine pity with the brandish of power [which] explains why the powerful are more inclined to be generous than to grant social justice."

H ow can philanthropists break abroad from this default position? Past nurturing the plurality of voices that are essential to agree both government and the free market to account. Philanthropy tin can even act every bit an agent of resistance, the American historian of philanthropy Benjamin Soskis suggested, immediately subsequently the election of Donald Trump. "The cardinal liberal values, those of tolerance and respect for others, of decency, clemency, and moderation, take been enfeebled in our public life," Soskis said. "Philanthropy must be a place in which those values are preserved, dedicated, and championed."

Philanthropy can recover a genuine sense of altruism but by understanding that it cannot do the job of either government or business. For it belongs not to the political or commercial realm, but to civil club and the world of social institutions that mediate between individuals, the marketplace and the state. It is true that philanthropy tin weaken elected governments, especially in the developing world, by bypassing national systems or declining to nurture them. And it can favour causes that but reverberate the interests of the wealthy. Simply where philanthropists support community organisations, parent-teacher associations, co-operatives, faith groups, environmentalists or human rights activists – or where they requite straight to charities that address inequality and specialise in advocacy for disadvantaged groups – they can assistance empower ordinary people to challenge authoritarian or overweening governments. In those circumstances, philanthropy can strengthen rather than weaken democracy.

But to exercise this, philanthropists need to be cannier about their analysis and tactics. At nowadays, most philanthropists with concerns about disadvantage tend to focus on alleviating its symptoms rather than addressing its causes. They fund projects to feed the hungry, create jobs, build housing and ameliorate services. But all that good piece of work tin can be wiped out by public spending cuts, predatory lending or exploitative depression levels of pay.

And there is a deeper problem. When it comes to addressing inequality, a well intentioned philanthropist might finance educational bursaries for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, or fund preparation schemes to equip low-paid workers for better jobs. That allows a few people to leave bad circumstances, simply it leaves countless others stuck in under-performing schools or depression-paid insecure work at the lesser of the labour market. Very few concerned philanthropists think of financing research or advocacy to address why and then many schools are poor or so many jobs are exploitative. Such an approach, says David Callahan of Within Philanthropy, is similar "nurturing saplings while the wood is being cleared".

By dissimilarity, conservative philanthropists take, in the by 2 decades, operated at a dissimilar level. Their agenda has been to modify public argue then that information technology is more than accommodating of their neoliberal worldview, which opposes the regulation of finance, improvements in the minimum wage, checks on polluting industries and the establishment of universal healthcare. They fund climate modify-denying academics, support complimentary-marketplace thinktanks, strike alliances with bourgeois religious groups, create populist TV and radio stations, and fix "enterprise institutes" inside universities, which allows them, not the universities, to select the academics.

Research past Callahan reveals that more than liberal-minded philanthropists have never understood the importance of cultivating ideas to influence key public policy debates in the fashion conservatives have.

Only a few peak philanthropic foundations – such as Ford, Kellogg and George Soros' Open Order Foundations – give grants to groups working to empower the poor and disadvantaged in such areas. Most philanthropists encounter them as too political. Many of the new generation of large givers come out of a highly entrepreneurial business organisation world, and are disinclined to back groups that challenge how commercialism operates. They are reluctant to back groups lobbying to promote the empowerment of the disadvantaged people whom these aforementioned philanthropists declare they intend to assist. They tend not to fund initiatives to alter taxation and financial policies that are tilted in favour of the wealthy, or to strengthen regulatory oversight of the financial manufacture, or to change corporate culture to favour greater sharing of the fruits of prosperity. They rarely think of investing in the media, legal and bookish networks of central stance-formers in social club to shift social and corporate culture and redress the influence of conservative philanthropy.

Rightwing philanthropists have, for more than two decades, understood the need to work for social and political modify. Mainstream philanthropists now need to awaken to this reality. Philanthropy demand not exist incompatible with republic, just information technology takes piece of work to ensure that is the case.

This is an edited extract from Philanthropy – from Aristotle to Zuckerberg past Paul Vallely, published past Bloomsbury on 17 September and available at guardianbookshop.com

This commodity was amended on 9 September 2020 to clarify that other forms of ID apart from a driving licence can be used to vote. It was further amended on x September 2020. An earlier version said a quote alarm almost the growing influence of rich donors had come up from the UN general associates; it has now been correctly attributed to the Global Policy Forum.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/sep/08/how-philanthropy-benefits-the-super-rich

Posted by: wrightdemusbace.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Money Do The Rich Give To Charities"

Post a Comment